I look up, squinting through the hot, merciless sunshine. I see a yellow star against a sea of red, flapping in the rhythm of the wind, cast on the blue summer sky.

We are in Vietnam, the S-shaped country that stretches vertically on the map, a socialist country whose recent history has been fraught with decades of endless power struggles, stricken with poverty at various points during the past half century, a nation that is at once captivating yet simultaneously difficult to swallow.

Want to save this recipe?

Enter your email & I'll send it to your inbox. Plus, get great new recipes from me every week!

More precisely, we are in Ho Chi Minh City, formerly known as Saigon before the North and the South of the country were unified in the mid-1970s.

I didn’t know much about Vietnam apart from the fact that it produced a vast amount of rice in its padi fields and that it was famous for its thick, strong coffee. But on my 5-day trip to the city in South Vietnam with my parents, I find myself trying to understand this country, its people and its history all in one condensed lesson.

It is end-April, and my parents and I land at the airport smack in the middle of Vietnam’s dry season, which typically runs from January to September. Temperatures are high, there is little rain, and humidity covers you like a thick heavy blanket.

If you ask me what stands out about our time in Ho Chi Minh, I’ll tell you that I remember the intense heat that beats on your back and strikes your face anywhere that shade does not cover; and I’ll also tell you about the feeling of constant perspiration that stays with you for as long as you are not in an air-conditioned room. It is hot, humid, hot. Now I understand why the locals wear their triangle hats.

Yet despite the unbearable heat, most locals are clad in long-sleeved tops and long pants, and many even wear face masks – a form of protection from the harsh UV rays and smog that fills the city.

Walking through the streets of the city, I am amazed at the endless streams of motorcyles and scooters that bombard you in every single direction.

Look everywhere before you cross the street, and cross neither too quickly nor too slow; you want to have time to react should a motorbike or scooter suddenly turns your way, but at the same time, give the rider time to spot you and find its way around you. Within two days, we begin to get the hang of crossing Saigon’s jam-packed roads, but still, my parents and I hold onto each other at every crossing: there is strength in numbers.

We take a tour to the Cu Chi tunnels, and on the bus there our tour guide Frank the Tank tells us jokes with a strict poker face. His description of the Vietnam war – the one which the USA took part in – gives me the impression that local Vietnamese are still suffering the effects of the war, and some are still not particularly fond of the North Americans.

We climb through just 40 meters of the tunnels that helped the guerrillas from the North of Vietnam win their battle against the Americans, and as the afternoon heat and trekking wear us out, I only wish for an ice-cold glass of water and an air-conditioned room. I recognize myself: a first world citizen and comfort of creature who is unable to withstand the impoverished conditions of war. I give thanks for not having to go through war, and deep down inside wonder if I would be able to survive an experience as traumatic as that. I don’t think too much. I doubt I can.

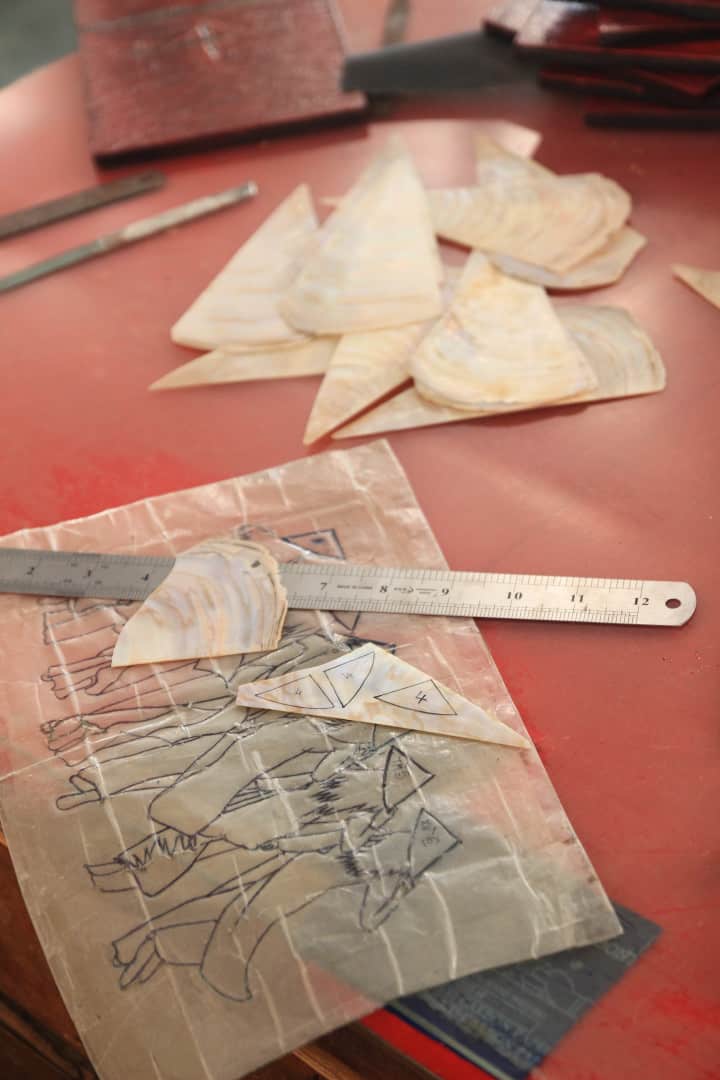

On the way back, we visit a lacquerware factory that is run by the military and employs veterans of war who were maimed in the Vietnam War. We are guided through the lacquerware-making process from start to finish, and we see the backbreaking work done by the employees who I hear only get a 15-minute lunch break every day, before they return to the grind. My heart aches for these people I don’t even know.

Later on, we head over to the Reunification Palace, whose inside spins a completely different story from the Vietnam we had just experienced. Inside it is grandiose and peaceful and beautiful. New and shiny and bright.

I am amazed at the stark difference lived by those in power versus its people.

That night, I buy the book “The Girl in the Picture” by Denise Chong from a roadside vendor. The author tells the story of Kim Phuc, the 9-year old girl who was badly burned in a napalm strike during the war, and how her life evolved long after the war had ended.

I find myself immersed in Chong’s writing, lost in 1970s Vietnam, as the communists in the North fight against the South Vietnam army and the US soldiers stationed there. I cringe at the raw description. I am appalled but cannot stop reading.

Over the next few days, we go to wholesale markets in search for objects worth importing back to Singapore – my parents are testing out an online business venture now that both of them are retired.

At An Dong market, my mom and I sit on low stools with the fan blowing hot air in our faces and sip from a bottle of cold water, as my dad negotiates to get a better price on account of the fact that we’re buying large quantities of lacquered products, typical of Vietnam.

When my dad closes the deal at a price he is happy with, we walk down to the basement hawker center, where being the only tourists eating lunch at 3pm in the afternoon, become prey to aggressive hawkers who each try to get us to patronise their stalls. I cannot understand a word of what they are saying, and for a moment I feel trapped, like a fish stuck in the net, frantically trying to escape.

Ho Chi Minh City seems to be filled with hawkers showing off their wares and goods; and at Ben Thanh market everyone is trying to earn their living, selling almost the same goods with price being the only differentiating factor. The storekeepers tug at our arms as I walk by, and unconsciously I flinch, feeling the lack of personal space. They pull us towards them, and speak to us in all sorts of languages, trying to guess where we’re from, trying to reel us in. I guess I understand why they’re as aggressive as they are; there is no other way about it.

On our last day before flying back to Singapore, we walk around District 1, where our A&EM Corner Hotel is located. I take my camera with me and put on the zoom lens, hoping to capture a bit of Vietnam, a souvenir for my trip. I snap a little here and there, sometimes asking for permission from the locals, sometimes just shooting from afar.

Vietnam seems stuck in the past; what I would imagine Singapore would have looked like in the 1980s.

It feels old, like a sepia photograph, with the color faded away. A photo that is struggling to fill itself with color and keep up with the 21st century. I wonder what the next few decades will look like for Vietnam.

I think I would like to return next time, to the North. Maybe, someday in the future, I’ll make another trip.

What an engaging post.Love your pictures.

Thank you for sharing.

Agnes

findinglifebalancewithagnes.blogspot.com

Thanks Agnes! Thanks for stopping by! 🙂

Hi Felicia,

What a vivid picture you have so realistically described our visit to Vietnam in the above post. I love reading what yo wrote as it brought back memories of our days spent together in Ho Chi Minh City.

Yeah, maybe another time we will explore more of Vietnam in future trips.

Love you lots 🙂

Mum

Yep! next time we can explore more of Vietnam or maybe even other parts of Asia 🙂 Love you lots too mummy!!